Does the menstrual cycle influence the effect of chemotherapy?

Researchers call for more women-specific drug research

A team of Dutch and Belgian researchers from the Netherlands Cancer Institute, Oncode Institute, and the VIB-KU Leuven Center for Cancer Biology has found that the menstrual cycle phase may influence the effectiveness of chemotherapy in breast cancer. The finding highlights the importance of further research into the menstrual cycle, the effects of drugs on women versus men, and female-specific research in general.

Women have historically been underrepresented in drug research, except for female-specific diseases such as breast cancer. This is partly due to the complexity of the menstrual cycle, where fluctuations in hormone levels can affect results. Also, researchers are concerned about possible damage to egg cells or unborn children. Therefore, medical research still concentrates much more on male subjects and animals. The rationale is that those research models provide less hormonal variation that could influence results. But, as a consequence, there is also much less knowledge of how drugs work in women.

Blind spot

The effect of the menstrual cycle on the body is more significant than previously thought. “Scientists are only now beginning to realize this,” says Sabine Linn, an internist-oncologist at the Netherlands Cancer Institute. “It is becoming increasingly clear that there is a blind spot in drug research.”

Jacco van Rheenen, a researcher at the Netherlands Cancer Institute and Oncode Institute, became aware of this blind spot only when two researchers in his group pointed out a striking finding. “We were studying how chemotherapy can alter cancer cells, making them more resistant to therapy. But we only saw this difference in some of the mice; in others, it didn’t seem to happen. And we know that women with breast cancer respond variably to chemotherapy, but we don’t know why that is.”

Different phases

The two researchers suggested that the estrous cycle, the mouse version of the menstrual cycle, may play a role. “They suggested that the measurements were perhaps taken during different cycle stages. At first, I didn’t pay much attention to it. I didn’t think the cycle would greatly affect the cells. But when I showed the results to my wife, she said, ‘That makes sense, right? Of course, there could be an effect!’ That got me thinking. We then started mapping this in more detail.”

Meanwhile, other recent research by Van Rheenen and Colinda Scheele, researcher at the VIB and KU Leuven, and their colleagues showed that the menstrual cycle influences the behavior of breast (cancer) cells. Now, he is convinced the cycle has more influence on the body than previously thought. “At medical conferences, I notice that these findings evoke different reactions. Some colleagues, especially men, react skeptically, as I did initially. But many women agree and recognize the possible influence of the cycle.”

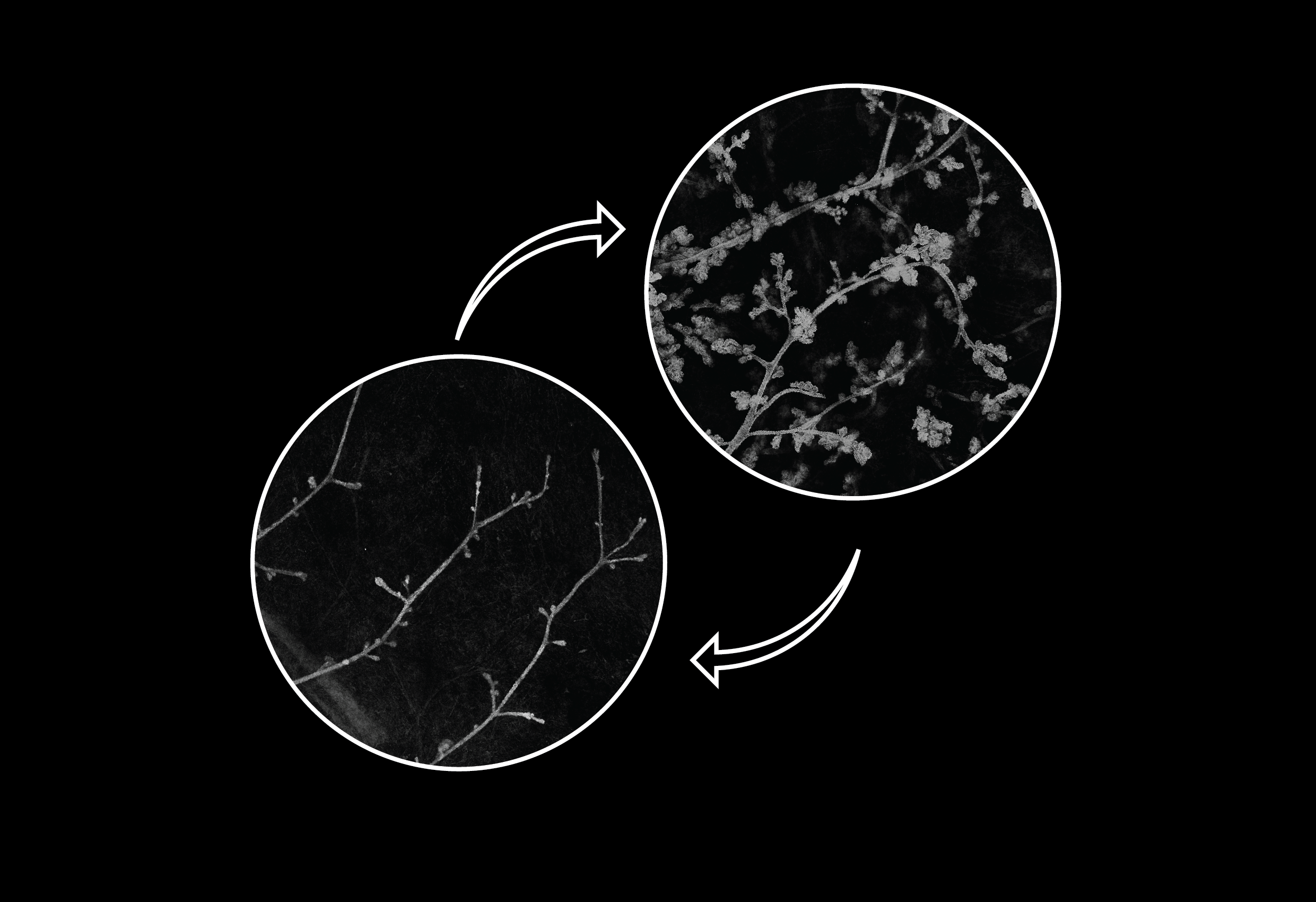

Sensitive to chemotherapy

The team of researchers found that the estrous cycle affects the sensitivity of breast cancer to chemotherapy. “We saw that there was a sensitive phase of the cycle in which the chemotherapy killed more cancer cells,” says Scheele, who is again collaborating with van Rheenen in this study. “That sensitivity to the chemotherapy remained, even after the cycle stopped because of the treatment. In short, the moment of administering the first dose of chemotherapy was important for the effect.”

The researchers already knew that chemotherapy works better when a certain type of immune cells is less present in the breast tissue. “We saw that the level of immune response in that tissue varied per phase,” says Scheele. “The permeability of the blood vessels, through which the chemotherapy enters the tissue, also appeared to depend on the moment in the menstrual cycle.” Finally, the sensitivity of the cancer cells to the treatment also differed per phase.

New patient study

The researchers checked these findings in previously recorded data from 55 treated women. “We found evidence that even in women with breast cancer, the menstrual cycle played a role in the effectiveness of chemotherapy,” says Van Rheenen. “That’s an interesting finding. But because the group was small and we did not set up the study specifically for this question, we cannot yet draw a definitive conclusions from this.”

That’s why the researchers are now setting up a national study funded by Oncode Institute. “We want to specifically study the treatment of women with triple-negative breast cancer because their treatment regimen starts with chemotherapy,” says Linn. “In 100 women, we aim to draw one extra tube of blood just before chemotherapy. That will allow us to determine where these women are in their cycle, analyze in whom the treatment works well, and whether there is a link between treatment outcome and the menstrual cycle. Nothing changes about the treatment itself.”

Unborn child

The researchers anticipate that some drugs may work better in one phase of the menstrual cycle than another. “Just think about the many changes occurring in a body under the influence of hormones,” says Van Rheenen. “For one, they cause fluctuations in body temperature, affecting your blood circulation.” Linn adds that the immune system also has an effect. “The cycle prepares the woman for a possible pregnancy. An unborn child is based half on foreign material from the father. It can only grow if the immune system is tolerant at that time.”

“I hope that in five years, we will have a better understanding how the menstrual cycle affects chemotherapy,” says Linn. “That hasn’t been addressed before. This study highlights the importance of research on the cycle and women-inclusive medical practice in general.” Scheele agrees: “More research in this area will ultimately lead to better health for the female half of the world’s population.”

Publication

The oestrous cycle stage impacts mammary tumour sensitivity to chemotherapy. Bornes, et al. Nature, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08276-1.

Funding

The research (team) was supported by the Boehringer Ingelheim Foundation, an EMBO postdoctoral fellowship, The Beug Metastasis Prize, Flanders Research Organization (FWO), The Ammodo Science Award, Doctor Josef Steiner Foundation, and The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

India Jane Wise

Over het VIB-KU Leuven Centrum voor Kankerbiologie

Kanker heeft vele oorzaken. Vaak gaat het om een combinatie van levensstijl, omgevingsfactoren en variaties in de genen. We moeten kanker op verschillende fronten bestrijden, en dat kan alleen op basis van kennis. Onderzoekers van het VIB-KU Leuven Centrum voor Kankerbiologie ontrafelen nieuwe mechanismen om zo specifiekere opsporingstechnieken én behandelingen te ontwikkelen.